Procol HarumBeyond |

|

|

PH on stage | PH on record | PH in print | BtP features | What's new | Interact with BtP | For sale | Site search | Home |

|

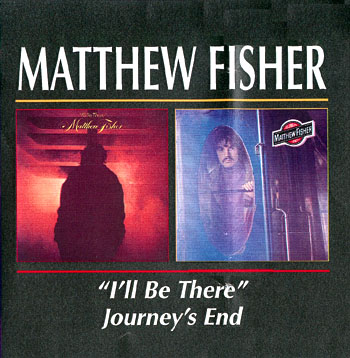

Journey's End

I'll Be There

In October 1967, as Procol Harum's follow-up to A Whiter Shade of Pale was riding high in the UK singles chart, The New Musical Express proclaimed that 'organist Matthew Fisher is to make an LP without the other members of the group'. Fisher's artful Hammond had hallmarked an absolute classic of the era, so this solo-album was eagerly awaited: yet as the months

the years

passed by, Matthew appeared more and more committed to group-work, contributing more songs, vocals, and instruments to each successive Procol album, ultimately emerging as producer of their masterpiece, A Salty Dog.

Privately, however, he was less than happy in Keith Reid and Gary Brooker's ensemble, which he left in 1969: work started on a solo project for A&M, which he aborted, and his talents surprisingly faded from public view. He ran a small demo-studio in Kingston-upon-Thames, then worked a while at CBS in New York; he returned in 1972 to guest on Jerry Lee Lewiss London sessions, to play with David Bowie at the Rainbow, and to produce the album that launched fellow ex-Procol Robin Trowers solo career.

When RCA eventually did release a Fisher solo album in the late summer of 1973, Rolling Stone raved that 'Journey's End is one of those rare albums in which the first few seconds of the first track are enough to convince the listener that something exceptional is going on.' In the UK a more guarded NME found that ' it deserves more attention than it is likely to receive.' Nobody mentioned that Matthew's American manager, foreseeing massive sales, had already booked him a prospective tax-exile into RCA's Rome studios, where with some scarcely-auditioned cohorts he had recorded the hasty sequel, I'll Be There. Regrettably neither album was to join Bowie, Elton, Rod, Slade or the Stones in the charts of the day: and having fulfilled a two-disc contract with RCA, Fisher did not record solo again for another six years.

Journey's End is a smooth-sounding album (thanks to Beatles engineer, Geoff Emerick), while I'll Be There is relatively raw: yet their music has much in common. Many themes for the second were incubating during work on the first, and Matthew's method throughout was to lay down each song's rhythmic core alongside his session bassist and drummer, then take the 16-track tapes to various overdub studios for multi-instrumental layering, a process he loved. His plaintive voice with its unfashionably-clear diction was occasionally reinforced by studio treatments. He also composed lavish string and brass arrangements, even conducting the second batch, and produced both albums: it was close to being a one-man show.

Fisher had seemed to be the 'classical' member of Procol Harum, yet his solo oeuvre generally avoided that epic, weighty style, showing instead an unexpected aptitude for poppy hooks, modulating middle-eights, and vocal harmonies, none of which commerciality Procol had favoured. He now came forward as a polished Strat-player, also turning an accomplished hand to bass, harmonica, vibes and percussion as required. Less unexpected was the fertile, tasty work on all sorts of piano, and the immaculate trademark organ (a Lowrey Lincolnwood on Suzanne, Hammond M100 on the rest of the first album, Hammond RT3 on the second).

That early NME had primed us for an album mostly of instrumentals, and this collection contains four, the standout being Separation, whose Bach-like progressions date back to 1967: director Jack Bond had wanted the hit sound of Pale recreated for his film's opening credits, and Matthew had been toying with this haunting theme at that time. Song Without Words also pre-dates the abandoned solo-project, none of which, incidentally, was ever resurrected.

Fisher's songs digest quite a range of classy influences: Dylan (Cold Harbour Lane), Lennon (Hard To Be Sure), the Beatles (notably It's So Easy), Brian Wilson (Song Without Words), Booker T (Interlude), Elton John (Not Her Fault), even Simon and Garfunkel (Not This Time). The riff-driven experiment of It's Not Too Late (reminiscent of Roy Wood) was re-recorded after the Rome sessions with a different frankly better rhythm section, also heard on She Knows Me, a late composition that replaced an unsatisfactory instrumental. These two songs feature guitarist Mike Japp, with whom Matthew briefly contemplated forming a band. But he never planned to perform these songs live: 'My voice wouldn't have taken it, night after night,' he admits. 'I really don't see myself as an entertainer.'

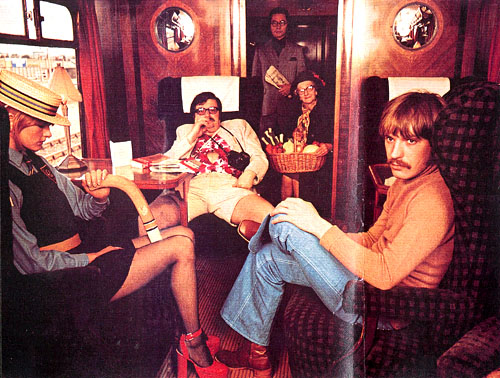

This much was confirmed in the album-jacket photography, by fashionable portraitist David Bailey. For Journey's End he posed Fisher among some cheerless models in a defunct Pullman carriage at London's Finsbury Park station, while I'll Be There stood him facelessly before a gallows of unmarked signposts (' of course they used the shot I liked least of the whole batch.') These downbeat images did, however, accurately reflect the alienated, directionless mood captured in many of the songs.

Fisher-fans doubtless supposed that his solo lyrics would prove as mysterious as those he had sung in Procol Harum; but Matthew now unveiled an utterly direct and unpretentious written style, matching the intelligence and substance of the music, which always came to him first. In contrast to his instrumental assurance, these words revealed wildernesses of anxiety, scrutinising flawed relationships, personal and professional, with harrowing honesty. Suzanne and Marie were built on recollections of a doomed early romance (' a bit of inspiration like that, you milk it for all it's worth I grasped the feeling and extended it'), while other songs, like Play The Game and Not This Time, similarly grew out of Procol hurts and disappointments.

Back in 1967 Fisher had stated his ambition, both professional and private, as 'recognition from people I admire': two songs now exposed his anguish at not being listed as Pale's co-writer alongside Brooker and Reid. Harum aficionados found Going For A Song and Journey's End Part 1 as shocking as Lennon's revisionist How Do You Sleep had been to McCartney fans. One was sung from a conjectural Brooker perspective, the other focused on Reid's own lyrical preoccupation with seeing truthfully. The mordantly-titled Going For A Song re-used Procol motifs from Whiter Shade, Pilgrim's Progress and Rambling On (the "if you realize just what I'm trying to say" melody), while Matthew's crucial "it really brings me down" was harmonised by the aggrieved ex-Procol drummer whose Pale session had been passed over by the smash-hit's producer. Journey's End recycled the opening of Procol's Repent Walpurgis (a group composition for which Fisher felt he'd been given writing-credit 'as a booby prize') and pointedly revisited the band's classic sound-world, moving from churchy piano and organ to a tumultuously-orchestrated grand finale. Bitter stuff.

'This was how I felt, not how I now think things were,' Matthew explains. 'There was never a big hate scene [in Procol] mutterings of discontent, that's as far as it ever got.' In fact Taking The Easy Way Out, from the follow-up, already acknowledges his own, indecisive contribution to that discontent. Other songs broaden from specific to general grievances, most clearly Cold Harbour Lane (a South-London substitute for Desolation Row, selected from the AZ index); Not Her Fault (still crying out for a cover-version!) achieves a touching universality. The wishful-thinking title-track sends an avenging angel to prey on the guilt of unscrupulous high-achievers everywhere Nixon was one whom Fisher had in mind with a build-up and abrupt conclusion recalling Lennon's I Want You (She's So Heavy), Matthew's favourite Abbey Road number. He could see no end in sight, barring an explosion and even that went off at half-cock. 'It was symptomatic of the general mess I was in, trying to make sense of it all,' he remembers.

'Fisher is a genius,' Procol's hypeful producer informed Disc and Music Echo in October 1967. Thirty-three years on, this double collection finally extracted from RCA for CD release rather reveals Matthew as a gifted craftsman, transforming the influence of his finest contemporaries (and the sonorities of Elgar, Tchaikovsky and Songs of Praise) into an endearing, enduring self-portrait. He went on to record three further solo albums (Matthew Fisher and Strange Days are available on BGOCD 308) and to take his Computer Science degree at Cambridge University. Now a software-writer by profession, he has also reverted to his rightful organ-bench, reunited with Brooker and Reid in the 90s incarnation of Procol Harum.

Interviewed in August 2000, Matthew Fisher is happily reconciled to being ' a fantastic ingredient in a melting pot: I now know I'm not Dylan or Lennon ' As this liner-note goes to press he is about to play the first Procol concert of the new millennium, to the delight of his fanbase world-wide. In a sense, then, he has completed a cathartic round-trip, whose outcome puts a positive spin on the titles of these two chronicles of long-gone grief: Journey's End I'll Be There.

Liner note © Roland Clare, with thanks to Matthew Fisher, and to Claes Johansen

|

|

|

PH on stage | PH on record | PH in print | BtP features | What's new | Interact with BtP | For sale | Site search | Home |